Introduction

The Working Holiday Visa (WHV) program in Australia has long been widely regarded as an ideal way for young people to travel and earn a living. This program has lower entry barriers and easier access compared with other visa types. However, according to Hutchens (2024), WHV holders have faced instances of exploitation and systemic issues. Therefore, it is urgent to discuss the rationality and potential for improvement of this policy.

Context and Significance

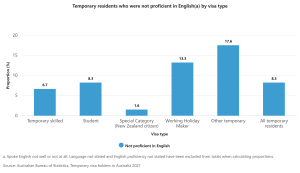

The WHV program has been popular among young people all over the world. According to the Australian Government Department of Home Affairs (2024), the number of WHV holders increases after the COVID-19 Pandemic, peaking at 179,437. Although the number of WHV granted rises steadily these years, WHV holders still face significant challenges in labour rights and working conditions. Job opportunities for WHV holders experience a 49.8% drop, with a loss of approximately 79,000 positions (ABS, 2021). Language barriers further compound these difficulties. 13.3% of WHV holders are not proficient in English, especially those born in China, who represent the largest group (ABS, 2011). These data highlight the importance to ensure fair employment and wages for WHV holders.

Source: Temporary residents who were not proficient in English(a) by visa type

Temporary visa holders in Australia, 2021 | Australian Bureau of Statistics

The condition experienced by many WHV holders cannot be overlooked. Coates et al. (2023) point out that many migrant workers are in a condition of low wages and wage deductions, and they also face greater risks of damage, such as bullying, sexual assault or injury. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the balance between solving the problem of labour shortage and labour exploitation.

Angle and Approach

This feature article aims at showing the multifaceted experiences of WHV holders, through interviewing with WHV holders, labour rights advocates, and policymakers, to explore the systemic challenges and potential reform ways.

Source: Agriculture and horticulture are high-risk sectors for migration worker exploitation in Australia, a UN official has warned. (Auscape/Getty)

Sources and Interviews

This article will interview WHV holders from a range of national backgrounds, exploring the challenges they face. The statements from government and official agencies are equally significant. Efforts will be made to communicate with the representatives from the Department of Home Affairs and the Fair Work Ombudsman to gain their interpretations, responses, and possible policy considerations regarding the WHV program.

Multimedia and Hypertext

This article will include some photographs of daily life and work scenes, provided by the WHV holders with their permission, to enhance the authenticity of sources and adoption of multimedia. External links including relevant policy documents, reports, and news articles will be embedded at appropriate points, strengthening its credibility and depth. Additionally, this article will make interactive visualisations by using the data from ABS, which enrich both the narrative and readers’ engagement with the article.

Source: What you need to know about Working Holiday visas in Australia | Pearson PTE

Target Publication and Audience

This article plans to be published in The Guardian Australia, which is known for its in-depth reporting on social justice issues. Our target audience includes WHV visa holders, policy makers, employer groups and Australia residents. Therefore, this article will resonate with the readers who are interested in immigration policies, labour rights, and international affairs.

Conclusion

This feature article will discuss the issue behind Australia’s WHV program, through first-hand stories, and expert insights, to find out the exploitation risks and policy challenges. With strong multimedia support and research, it aims to provide information for the Guardian’s socially passionate readers and contribute to the policy conversation.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021-22-financial-year). Jobs in Australia. ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/jobs/jobs-australia/latest-release.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021). Temporary visa holders in Australia. ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/temporary-visa-holders-australia/latest-release.

Australia Government Department of Home Affairs. (2024). Working Holiday Maker Visa Program Report. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/working-holiday-report-June-24.pdf.

Allan, S. (Ed.). (2022). The Routledge Companion to News and Journalism (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003174790.

Coates, B, Wiltshire, T & Reysenbach, T. (2023). Short-changed: How to stop the exploitation of migrant workers in Australia. Grattan Institute. https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Short-changed-How-to-stop-the-exploitation-of-migrant-workers-in-Australia.pdf.

Hutchens, G. (2024). Temporary migrant workers in Australia facing ‘disturbing’ patterns of exploitation from some employers, UN official says. ABC. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-11-27/slavery-in-australia-un-report-special-rapporteur/104652556.

Be the first to comment