Digital-born news organizations — organizations which originated from the Internet (Martin, 2019) — tend to do better multimedia online journalism coverage than legacy papers.

However, that is not always the case. Sometimes, legacy papers do better than digital-born organizations by making their articles easier to digest with multimedia and visually friendly content.

The New York Times

History/Production

The New York Times, commonly known as The Gray Lady, was established in 1851 as a daily newspaper in New York City in the United States. It has been a family owned paper since 1896 when Adolph Simon Ochs bought the paper. Currently, Ochs’ direct descendant Arthur Gregg Sulzberger is the deputy publisher, continuing on the family legacy (Thompson, 2018). It is not only a well-known national paper but a worldwide news organization.

Their website, NYTimes.com, was launched in 1996 — their content was available for free until March 2011 when the company established a paywall (Peters 2011). Readers who are not subscribed to the New York Times have a total of five free articles each month before hitting the paywall. (Garun, 2017)

Like many legacy newspapers, the New York Times’ website is mostly a copy of their print version. However, recently the Times has revamped their website — trying to make the front end of their website more multimedia friendly like a digital-born news organization.

Audience demographic

At the end of 2017, the Times had about 3.6 million paid subscriptions across more than 200 different countries and territories to their print and digital content (Thompson, 2018). Earlier this year, the Times announced it had 4.3 million paid subscribers, with 3.3 million of those subscriptions being for the digital content (Peiser, 2019).

The average reader of the Times is fairly young, usually skewing to be less than 30 years old (“In Changing News Landscape, Even Television is Vulnerable,” 2012). The majority of readers are college graduates and male (“In Changing News Landscape, Even Television is Vulnerable,” 2012).

While the Times may be an American news organization, 16 percent of their paid subscribers live outside of the United States (Peiser, 2019).

In 2017, the website averaged about 97 million unique visitors per month in the US. Globally, the website had a monthly average of 136 million unique visitors (Thompson, 2018).

BuzzFeed

History/Production

BuzzFeed, Inc is an American web-based company that was founded in 2006 by Jonah Peretti and John S. Johnson III as a way to track viral content. For its first several years, it was known for its online quizzes, listicles, and pop culture articles (“About BuzzFeed”, 2019) In 2011, Ben Smith from Politico was hired as editor-in-chief for BuzzFeed News, a new branch of the company which focused on newsworthy journalism (Tandoc & Jenkins, 2017). However, BuzzFeed News struggles to be recognized as a major news source by millennials, Americans and competing news organizations (Mitchell, Matsa, Gottfried & Kiley, 2014) due to its clickbait and viral past (Tandoc & Jenkins, 2017).

Unlike many other news organizations, BuzzFeed has no paywall or subscribers — it makes its revenue through ads and paid sponsored posts.

Audience demographic

While BuzzFeed has its own website, most of its audience finds its articles and content through social media such as Twitter and Facebook (Bradshaw & Rohumaa, 2017). It brought in about 88.52 million visitors in the last six months (“Buzzfeed.com Traffic Statistics,” 2019) and the majority of its audience is female (Hwong, 2018). The website is commonly known to attract millennials — according to an article by Business Insider in 2014, “more than 50% of US millennials read BuzzFeed per month.”

Coverage of Ethiopian Plane Crash

New York Times

The New York Times online delivery of the breaking news story of the Ethiopian plane crash on March 10 included a video, visual graphs, and photographs along with its text.

The coverage of the Ethiopian plane crash was very thorough with all the information available at the time. However, at some points, the article concentrated on the Lion Air incident too much, giving the reader unnecessary information such as “families of some of the victims of the Lion Air crash are suing Boeing.” The audience would likely be more interested in the Ethiopian plane crash, not the Lion Air one — it would have been better to exclude it or hyperlink an article that talks about the most current follow up of the Lion Air crash.

The reporter also included information about the new Ethiopian prime minister and his political reforms. This information was also not important to the story as a whole.

On a laptop or personal computer, the images can expand for better viewing. Unfortunately, the images are missing the alt text that provides context for readers who cannot see images on their browser (Bradshaw & Rohumaa, 2017).

The two-minute video plays automatically on a desktop, but not on mobile — which is good because sometimes readers who are reading the article on their phone might not be in an environment where they can listen to a video (even though it has captions). All links were functional, any links that redirected to another New York Times story would open on the same page, but any outgoing links would open on a new tab.

The graphs in the story highlighted the technical information in an easy visual format for the audience to understand the short distance the plane traveled as well as the plane’s unstable altitude and speed.

The story had no embedded tweets. It might have been better to include the FlightRadar24 tweet that was referenced. The link to Boeings’ Twitter statement was missing as well.

The story as a whole followed the classic inverted pyramid structure (Alysen, 2012) — it started with the most important information about the crash, and less important information about the airline was towards the bottom.

While it is an effective piece of online journalism, it was not entirely up to online journalism standards because the article was quite long with 1,700 words and there were no subheadings to make it more scannable for the reader. However, because the photographs and graphs broke up the text, it did not feel like a very long article (Bradshaw & Rohumaa, 2017).

The article was social media friendly, providing the reader with ways to share the story via Facebook, Twitter, email, LinkedIn, Reddit, or a short URL link. It also allowed for community engagement through comments, which are an important aspect of online journalism (Bradshaw & Rohumaa, 2017). But it did not provide a way to contact reporters via emails or Twitter.

Overall, the coverage of the initial Ethiopian plane crash was effective in engaging the reader and presenting all the information available with a bit of background of Boeing, the airline, the victims and the country.

BuzzFeed

BuzzFeed’s coverage of the Ethiopian airplane crash was not at the same level as the New York Time’s coverage of the same incident. Even though the images were powerful and the embedding of the tweets was accurate, it still was not enough.

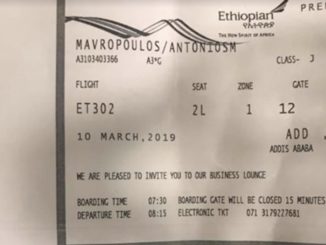

One of the main problems was that BuzzFeed failed to caption their two images. This may confuse the reader about who the people in the images were. For example, in the first image, there was a woman on the phone and she appeared distressed. Who was she? Why was she distressed? Was a family or friend on the plane that crashed?

If the reporter, Nidhi Subbaraman, had supplied that information it would have been easier to create a connection to the woman. In the second image, there was a man wearing a suit in the midst of the rubble. Same questions: who was he, what was he doing? Also, the images are missing the alt-text making them not search engine optimization friendly for search engines like Google (“Google Image best practices – Search Console Help,” n.d.).

The article was also missing a crucial hyperlink to an important source. It might have been better to include a link to a video of the press conference by Ethiopian Airlines CEO Tewolde Genremariam starting it at the time code where he was quoted. It was quickly found on YouTube, but it would have been more user-friendly if BuzzFeed hyperlinked to it instead.

Hyperlinks were used throughout the piece, but the reporter was not always using the appropriate keywords for the linked phrases either. All links, however, opened on a new tab, including the BuzzFeed news article about the Lion Air plane crash.

The tweets used throughout the news piece could have been better managed. For example, the reporter embedded the information from Ethiopian Airline’s bulletin one, but linked bulletin two in the text. This put emphasis on less important information.

Much like the Times’ article, BuzzFeed’s article follows the classic inverted pyramid — with the most important information at the top (Alysen, 2012), even including the information of some of the victims of the plane crash. However, it failed to inform its readers of the exact information of the problems of the plane, such as the unstable vertical speeds provided by FlightRadar24 on Twitter.

There should have been more than one person reporting on a major breaking news story of this magnitude — even if all the reporters were stationed in America.

The article is user-friendly, allowing the reader to share it on Twitter, Facebook or copy the link. It also allowed for commenting via Facebook, which gives an opportunity for community engagement. It also had a way to contact the reporter via email — unlike the New York Times article.

Overall, the coverage of the Ethiopian crash was brief and to the point, but it could have used more information and better use of multimedia and hyperlinks.

Conclusion

The New York Times coverage of the Ethiopian plane crash was a good example of what online journalism should be (Bradshaw & Rohumaa, 2017). It was not perfect, but it did better than its digital-born competition, BuzzFeed. However, I believe that BuzzFeed could have also had a strong online journalism piece like the Times if it had the same resources and number of journalists working on the story.

References

About BuzzFeed. (n.d.). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.buzzfeed.com/about

Alysen, B. (2012). The news story structure. In Reporting in a Multimedia World : An introduction to core journalism skills (2nd ed., pp. 173–191).

Bradshaw, P., & Rohumaa, L. (2017). The online journalism handbook : Skills to survive and thrive in the digital age. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au

Buzzfeed.com Traffic Statistics. (2019, February). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.similarweb.com/website/buzzfeed.com

Garun, N. (2017, December 01). The New York Times cuts free articles limit from 10 to five per month. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.theverge.com/2017/12/1/16724620/new-york-times-cuts-five-free-articles-paywall

Google Image best practices – Search Console Help. (n.d.). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://support.google.com/webmasters/answer/114016?hl=en

Hwong, C. (2018, March 07). Chart of the Week: Tracking Audience and Reader Demographics. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.vertoanalytics.com/chart-week-tracking-news-reader-demographics/

In Changing News Landscape, Even Television is Vulnerable. (2012, September 27). Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.people-press.org/2012/09/27/section-4-demographics-and-political-views-of-news-audiences/

Martin, F (2019). Online Journalism MECO6925: Week 2 Features, forms & functions [PowerPoint Slides]. Retrieved from https://canvas.sydney.edu.au/courses/14465/files/5616739?module_item_id=474598

Mitchell, A., Matsa, K. E., Gottfried, J., & Kiley, J. (2014, October 21). Appendix C: Trust and Distrust of News Sources by Ideological Group. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.journalism.org/2014/10/21/appendix-c-trust-and-distrust-of-news-sources-by-ideological-group/

O’Reilly, L. (2014, November 25). Millennials Are Switching Off TV In Favour Of … BuzzFeed. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.businessinsider.com.au/buzzfeed-reaches-more-millennials-than-us-tv-networks-2014-11?r=US&IR=T

Peiser, J. (2019, February 06). The New York Times Co. Reports $709 Million in Digital Revenue for 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/06/business/media/new-york-times-earnings-digital-subscriptions.html

Peters, J. W. (2011, March 17). The Times Announces Digital Subscription Plan. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/18/business/media/18times.html?_r=1

Tandoc, E. C., & Jenkins, J. (2017). The Buzzfeedication of journalism? How traditional news organizations are talking about a new entrant to the journalistic field will surprise you! Journalism, 18(4), 482–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884915620269

Thompson, M. (2018). The New York Times Company 2017 Annual Report(Rep.). Retrieved from http://www.annualreports.com/HostedData/AnnualReports/PDF/NYSE_NYT_2017.pdf

Be the first to comment