Background and Significance

In early 2024, the Group of Eight (Go8) adopted a new working definition of antisemitism based on the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) framework.

Although intended to address rising concerns about antisemitism on university campuses, the move has sparked criticism from academics, student groups, and civil society organisations. For example, the Executive Committee of the Australian Historical Association warned that the definition could place new limits on academic freedom. Meanwhile, the Executive Council of Australian Jewry argued the statement did not go far enough and called for full adoption of the IHRA definition. In contrast, supporters of the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism — including over 370 scholars of Holocaust and Middle East studies — maintain that antisemitism must be clearly separated from criticism of Israeli state policies to protect free and open debate.

The new definition of antisemitism is not the only move raising concerns about freedom of speech in Australia. Dr. Joo-Cheong Tham, a law professor at the University of Melbourne, told The Conversation that over the past year, all Go8 universities have tightened restrictions on campus protests. This wave of protest limitations has created a chilling effect, undermining universities as spaces for open debate, as staff fear job loss and students worry about academic penalties or career consequences.

Table of restriction examples, cited from The Conversation(2025).

News Feature Idea

This tension — between political neutrality and institutional power — reveals a deeper question: how far should universities go in regulating student expression, and at what cost?

In response, my feature will investigate how Australia’s top universities, particularly the Group of Eight, are reshaping the limits of political expression through new definitions of antisemitism and increasing restrictions on student protest. While these developments may appear confined to campus life, they in fact reflect a broader national shift in how dissent is managed within public institutions — raising urgent questions about academic freedom and the health of democratic engagement.

Given this context, I plan to pitch this feature to Crikey, an independent publication known for unpacking how power works in Australia. With a readership that is politically engaged, often older, and invested in the future of public institutions, Crikey offers the right platform to explore the civic consequences of silencing student voices in spaces that should encourage dissent and debate.

Story Entry Points

>>>>>>>>One entry point of the feature could examine specific university policies, such as the University of Sydney’s Campus Access Policy (CAP), which introduced new approval requirements for on-campus events and demonstrations.

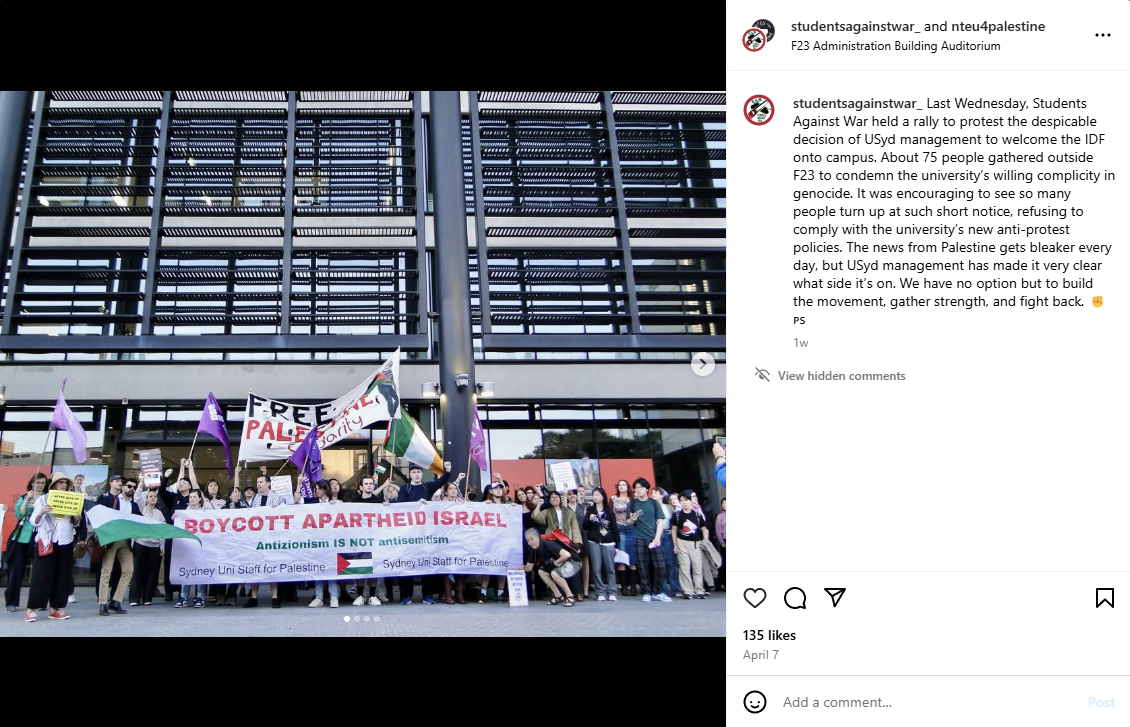

Another angle to explore is how students and staff are reacting and understanding these changes and new restrictions. Groups like Students Against War (SAW) have actively organised forums, petitions, and protests in opposition to policies they believe silence pro-Palestinian voices.

Further discussion could reflect on broader responses beyond campus, as legal experts and academics warn that universities are becoming increasingly risk-averse in managing political speech.

Possible Interviewees

1. Students Against War (SAW), to understand the on-ground impact of protest restrictions.

2. Dr. Joo-Cheong Tham, on legal and democratic implications.

3. Dr. Ryan Naylor and Prof. Murray Print, for academic context on student engagement.

Word Count: 507 Words

Be the first to comment